Namibia is a country located in Southern Africa. It has an area of 825,418 square kilometers and a population of approximately 2.6 million people. The ethnic composition of Namibia is mainly Ovambo, with other minority groups including Kavango, Herero and Damara. The majority of the population are adherents to Christianity, with around 80% following the religion and the rest being either Muslim or other faiths. Education is compulsory for children up to the age of 16 and the literacy rate is estimated to be around 73%. The official language is English but there are also many other languages spoken throughout the country such as Oshiwambo, Afrikaans and German. The capital city Windhoek has an estimated population of over 400 thousand people making it the largest city in Namibia. Check hyperrestaurant to learn more about Namibia in 2009.

Social conditions

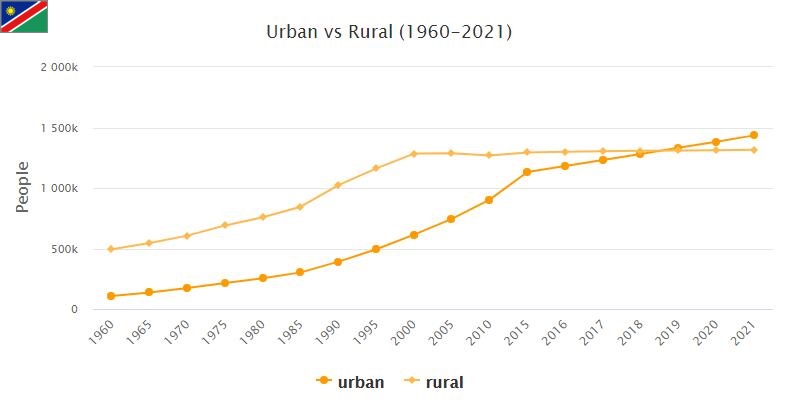

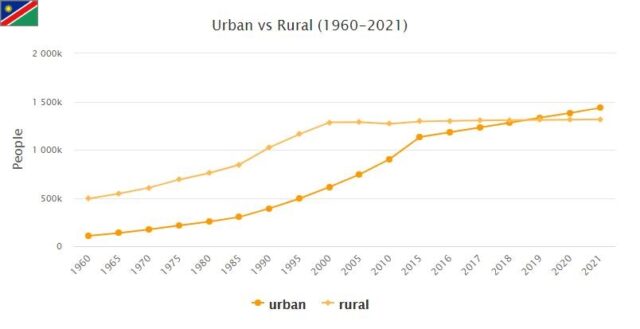

After the liberation from South Africa in 1990, an equality policy was introduced, but Namibia is still one of the world’s most unequal countries in terms of income distribution. Particularly large is the difference between those living in the capital Windhoek and the population of Ovamboland in the north. Poverty has fallen sharply in recent years. In 2010, 24 percent of the population lived below US $ 1.25 a day. At the same time, the richest tenth of the population controlled more than half of the country’s total income. Check to see Namibia population.

About 1/3 of the population is in need of food assistance. However, most (90 percent) have access to clean water. In the United Nations Development Index (HDI) 2014, Namibia is ranked 126 out of 188 countries and is thus estimated to have achieved medium-high development.

Namibia has been hit hard by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, just like most other countries in southern Africa; 13 percent of the population aged 15–49 are estimated to be infected (2009). Nevertheless, the average life expectancy is clearly higher than in other countries in the region. Several other social indicators also show that the country is better than the averages that apply to developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Qualified help is available in just over 80 percent of births. Maternal mortality is estimated at 130 per 100,000 births and the number of births per woman is 3.1 (2012). Visit AbbreviationFinder to see the definitions of NAM and acronym for Namibia.

In addition to education, health care is the largest item in public spending: 12 percent (2009). There are 27 hospital beds (2009) and four doctors (2007) per 10,000 residents, which is high figures for the region.

History. – After the dissolution of the Portuguese empire and the consequent independence of Angola and Mozambique (1975), Namibia, formerly South-West Africa, together with Rhodesia (independent in 1980 under the name of Zimbabwe) became the last bastion in defense of South Africa and its racist system. The status of this former League of Nations mandate was controversial. The UN had in fact declared South Africa collapsed since 1966, but all attempts to impose the authority of the highest international organization failed. South Africa itself followed parallel and non-communicating strategies: transformation of the territory into a province of the Republic of South Africa, creation of an ethnic-based state controlled by Pretoria, international negotiations.

To give substance to the hypothesis of an ” internal ” solution, in September 1975 the South African Prime Minister JB Vorster convened a conference, known as Turnhalle from the room where the meetings were held, in the context of which in March 1977 agreement was reached on a draft constitution for a provisional government with a view to independence. The national liberation movement, the SWAPO (South West Africa People’s Organization), officially recognized by the UN as a representative of the people of Namibia, did not give any credit to the initiative. The groups that had animated the conference founded the Democratic Turnhalle Alliance (DTA), a multi-ethnic coalition headed by a white man, D. Mudge, and supported by a series of tribal parties. A prominent member of the DTA, C. Kapuuo, chief of the Herero people, was assassinated in March 1978. Meanwhile (September 1977), Pretoria had appointed a general administrator to govern the territory, while UN pressure had intensified and of the same Western powers; The United States, Great Britain, France, Germany and Canada formed the so-called ‘contact group’ to deal informally with Pretoria.

In August 1978, the UN-appointed commissioner arrived in Namibia, but failed to put his nominal powers into practice. In September 1978 the Security Council passed Resolution 435 which provided for a multi-stage process to achieve the independence of the territory. The South African government continued on its way and announced the election of a constituent assembly. Pretoria, however, could not escape the negotiation procedure requested by its allies and in January 1981 a general conference was held in Geneva, under the aegis of the UN, between South Africa and SWAPO with the presence of the “ contact group ” and the states Africans called ” of the front ”. It lasted a week and ended with a total failure due to the intransigence of the South African government, who had perhaps wanted to take advantage of the possible international outcomes of the election of R. Reagan as president of the United States. In effect, since 1981, the US government has enforced the so-called principle of linkage, which linked the independence of Namibia to the withdrawal of Cuban troops present in Angola since 1975.

The Namibia was now one of the hotspots of the global confrontation and South Africa emphasized its role as an anti-Soviet pillar in Africa. Disagreeing with this approach, in 1983 France left the ” contact group ”. South Africa proved that it was unable to advance the internal solution. Both the central government and the local administrations it had established failed, and all power returned to the general administrator. Pretoria had Angola as its main interlocutor, alternating military interventions with negotiations. A first agreement with the Luanda government was reached in Lusaka in February 1984, but was not followed up. The United States was fully committed to mediation, always with the linkage clause relating to the Cuban forces, and in December 1988 South Africa, Angola and Cuba entered into a comprehensive agreement according to which the scheme envisaged since 1978 with resolution 435 was re-enforced.

The agreement provided for free elections and independence for the Namibia South Africa would withdraw its troops from Angola; Cuba would have moved north and gradually reduced its military contingents in the African state until complete withdrawal. The UN, present with a special representative and a corps of “blue helmets” (UNTAG), would have watched over the whole process. The elections were held in good conditions of freedom and security in November 1989: the SWAPO obtained 57% of the votes and 41 seats (out of a total of 72); the Democratic Alliance of Turnhalle, on which the South African government and the whites had focused, 29% of the votes and 21 seats. Not having the necessary two-thirds majority according to the agreements to draft the new Constitution, SWAPO and its president, S. Nujoma, having returned home after almost 30 years of exile, they launched a policy of extensive agreements, which ensured Namibia a certain stability, albeit at the cost of confirming the interests of the large white economic groups. The Constitution was adopted without opposition in Parliament. SWAPO’s victory in the 1992 local elections is a guarantee of the unchanged popularity of the former liberation movement.