New Zealand is a country located in the South Pacific. It has an area of 268,021 square kilometers and a population of approximately 4.9 million people. The ethnic composition of New Zealand is mainly European, with other minority groups including Maori, Asian and Pacific Islanders. The majority of the population are adherents to Christianity, with around 55% following the religion and the rest being either Hindu or other faiths. Education is compulsory for children up to the age of 16 and the literacy rate is estimated to be around 99%. The official language is English but there are also many other languages spoken throughout the country such as Te Reo Maori, Samoan and Tongan. The capital city Wellington has an estimated population of over 400 thousand people making it the largest city in New Zealand. Check hyperrestaurant to learn more about New Zealand in 2009.

Social conditions

New Zealand developed until the 1990s into a welfare state with growing budget deficits. However, the economic crisis hit the country hard, and in 1991 unemployment was 11 percent. Visit AbbreviationFinder to see the definitions of ZK and acronym for New Zealand.

The economy recovered slowly for two decades. Unemployment fell and was down 3.5 percent in 2008. However, the global financial crisis in 2008 also posed a severe strain on the economy and led to rising unemployment. In order to create more jobs, large investments were made in infrastructure, which led to an increase in government debt. In 2010, a budget deficit emerged after almost a decade of surplus in the Treasury, with the effect that the government made sharp cuts in health care, schooling and care.

Growth has increased until 2016 but is still sensitive to fluctuations in the world market.

Labor market

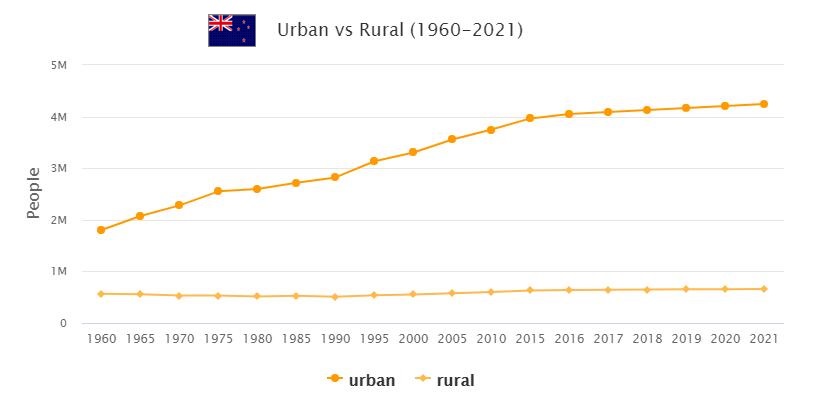

Unemployment in New Zealand has been fairly stable for a period and was 5.2 percent in 2016. Check to see New Zealand population.

The lack of highly educated labor has created greater opportunities for women, Maoris and Polynesian immigrants to take a place in the labor market. Women nowadays work almost as much as men. Although the law prohibits gender discrimination, the woman’s average salary is generally significantly lower than the male’s.

However, many women have reached high political positions. Nearly a third of Parliament’s members were women after the 2011 elections and in 2005–06 women were found in positions such as Head of State, Head of Government, President of Parliament, Governor General and Supreme Court President.

New Zealand has had a traditionally strong trade union movement. In the past, union membership has been mandatory, but this was abolished by the bourgeois government in the early 1990s. Furthermore, the right to strike was limited at the same time as the central negotiation system was terminated. Working hours were deregulated by the then bourgeois government. Previously, the working week was 40 hours, but after 1991 many work more than 50 hours per week. Since 2007, employees have been entitled to four weeks’ holiday.

During Labour’s reign of 1999–2008, the weakened trade union movement regained some power. For example, workers were again entitled to collective bargaining. Nowadays, every fifth worker is unionized.

Unemployment insurance exists for people who have been resident in New Zealand for at least two years. The remuneration is income tested and assumes that the unemployed are actively seeking work.

New Zealand introduced an old-age pension as early as 1898. It was then valid for 65 years and was needs tested. For a period, the retirement age was reduced to 60 years for poor and worn-out body workers. The retirement age has gradually been raised and in 2001 it was again 65 years. In 1977, the state pension needs test was removed.

Welfare and poverty

In 2015, the median income in New Zealand was SEK 14,300 per month. The median salary was SEK 20,300 per month.

Since the beginning of the 1980s, the number of poor people has risen. In 2015, more than 16 percent of the country’s residents were poor. Above all, child poverty has become a problem for New Zealand. Twice as many children as 1984, almost 20 percent of all children, live in poverty, which means that they live in families where income is lower than 60 percent of median income.

In New Zealand, child poverty manifests itself because children have a significantly lower standard of living and limitations in their lives. Child poverty means that children are sometimes homeless but also that they cannot participate in activities, have access to a healthy diet, accommodation, full education and hopes for the future.

Inequality in the country partly follows ethnic divides in New Zealand. There is an over-representation of Maoris and immigrants from island states in the Pacific in the unemployment and poverty statistics. Among these, violence against women and other crimes is also more frequent. The Maori life expectancy, which is about ten years shorter than the remaining population, also testifies to the social and economic differences between groups. However, there are also poor people of European descent.

Indigenous rights, especially their fishing rights and land rights, have been a contentious issue in New Zealand. In 2010, the bourgeois government signed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The decision was controversial and met with resistance within both his own party and Labor and the government’s support party ACT.

Like social security benefits, social insurance is customized to the needs and requires a certain length of stay in the country to apply.

Health care is largely tax-financed. Parts of healthcare are free or subsidized, while other costs are covered by private insurance. Nearly a quarter are covered by private insurance.

As long as their cases are pending, asylum seekers are entitled to state-funded health care. Similarly, the children of the paperless are entitled to schooling. Non-residents, as well as the paperless, must pay full health care costs unless their state of health is not the result of an accident. In such circumstances, care is covered by the state.

Abortion is only allowed when the fetus is damaged or if the woman’s condition is life-threatening. Pregnancy as a result of rape or if the mother is very young are also accepted reasons for abortion.

Since 2004, gay and heterosexual couples have the same rights regarding the custody of children, tax rules and social welfare. Same-sex marriage became legal in August 2013.

Family benefits

In New Zealand, parents are entitled to 18 weeks of paid parental leave. However, this can be extended to 52 weeks but the time that exceeds the first 18 weeks is then unpaid. Parental leave can be divided between both parents.

Most children in New Zealand, around 95 percent, have some form of childcare. This is usually 20-22 hours a week. The first 20 hours of childcare per week are state-funded from the age of 3 until the children start school after they turn five. This applies regardless of whether the children have a visa or not. Both teacher and parent-led child care exist.

Like the pension, the child allowance is a benefit of an old date. In the 1940s it became commonplace, but in 1985 it began to be tested again. The child allowance was completely abolished in 1991, when tax incentives for low-income families were introduced instead. Since 2005, a family package also exists, which has improved the situation for many families in a country where child poverty is relatively extensive.