Peru is a country located in South America. It has an area of 1,285,216 square kilometers and a population of approximately 32 million people. The ethnic composition of Peru is mainly Mestizo, with other minority groups including Amerindian, Afro-Peruvian, Asian and European. The majority of the population are adherents to Christianity, with around 85% following the religion and the rest being either Jewish or other faiths. Education is compulsory for children up to the age of 14 and the literacy rate is estimated to be around 94%. The official language is Spanish but there are also many other languages spoken throughout the country such as Quechua and Aymara which are both indigenous languages as well as over 50 other native languages. The capital city Lima has an estimated population of over 10 million people making it the largest city in Peru. Check hyperrestaurant to learn more about Peru in 2009.

Social conditions

Like most other countries in South America, Peru is characterized by great social differences. Visit AbbreviationFinder to see the definitions of PER and acronym for Peru. The standard of living varies widely depending on class, ethnic affiliation and between regions. The Spanish-speaking miseries make up the majority of a large and growing middle class while many of the country’s indigenous people live in extreme poverty. Few of those in the lower working class have an income that exceeds the official poverty line.

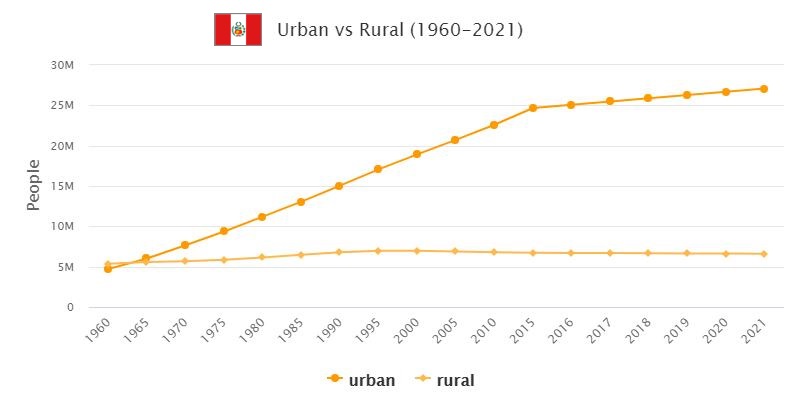

Thanks to strong economic development in the 2000s, the percentage of Peruvians living below the national poverty line has dropped significantly, from almost 60 percent in 2004 to about 25 percent in 2012. However, the large class differences make poverty most prevalent, especially in rural areas. Check to see Peru population.

Already difficult social conditions are also affected by the country’s exposure to natural disasters such as earthquakes and landslides that regularly destroy agriculture and infrastructure. Efforts are being made from the government to improve access to health care, for example, but the shortage of doctors, nurses and healthcare facilities is still great. Access to health care is hardly as in rural areas.

The social insurance system has been developed in recent decades, but insurance is still mainly linked to employment, which leaves unemployed and those working in the informal sector uninsured. During the 2000s, reforms were carried out with a view to offering all Peruvians basic health insurance.

Full retirement pension is due at age 65, under the condition that you have worked for at least 20 years.

In August 2012, the government created the National Office for Dialogue and Sustainability, which is to seek peaceful solutions to the social conflicts that are otherwise traditional than violence and killing. The number of people killed in the social conflicts subsequently dropped drastically, but the government was still unwilling to investigate the circumstances of the previous killings and to hold those responsible in the security forces accountable.

Also in August, the government proposed restrictions on freedom of expression. The reason was that a small group was active around the requirement for amnesty for members of the Luminous Path. Acc. The proposal would cost 6-12 years in prison to “deny” crimes committed by “terrorist organizations”. If the “denials” were broadcast over social media or other IT technology, the penalty frame was extended to 15 years. In addition, the country’s judges routinely pass judgments on “reproach” reporters. In May 2013, for example, a judge in Huaraz handed down Ancash. a conditional sentence of 2 years in prison over journalist Alcides Peñaranda from Integración magazine for “defamation” by Ancash Governor César Alvarez. The judgment also ordered Peñaranda to pay compensation to the governor. The background was an article in the magazine addressing corruption in the local government.

In August 2013, a Human Rights Ombudsman released a report on the 10th anniversary of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report. The Ombudsman concluded that despite initial attempts, he had failed to establish a legal system that could investigate the numerous cases during the 20-year dirty war and bring those guilty to justice. Out of the 194 cases the Ombudsman followed, 113 had been closed and only 32 had been sentenced.

In June 2013, the Constitutional Court issued a ruling concluding that the 1986 massacre at the Fronton prison, which cost 130 prisoners life, was subject to the limitation period because there were no crimes against humanity. The order completely violated an order of the 2000 Inter-American Human Rights Court (IAHCR), which ordered Peru to conduct an investigation into the massacre and bring those guilty to justice. In September, the Justice Department called on the Constitutional Court to change its ruling as it did not take into account the IAHCR’s ruling, and the question of whether the massacre constituted a crime against humanity was beyond the court’s judgment on the matter.

Throughout the 1990’s, the state conducted forced sterilization of hundreds of thousands of peasant and Native American women. This was confirmed by a parliamentary commission of inquiry in 2002. In January 2014, the Lima Prosecutor’s Office decided to raise just one case out of 2,000 cases raised by forcibly sterilized women. The decision to ignore the many cases led to national and international protests.

In September 2014, 4 Native American leaders Edwin Chota Valera, Jorge Ríos Pérez, Leoncio Quinticima Meléndez and Francisco Pinedo were killed as they headed to a meeting in the Ucayali region of the Amazon to discuss the illegal logging of the area. The Asháninka people are waging a permanent war against the companies that illegally invade their territory to trap rainforests.

On days 1-12. December 2014 the UN Climate Conference COP 20 was held in Lima. The conference was held in the shadow of rising oil production in the oil-producing countries. Australia’s fast-growing coal extraction. The failure of the conference made it clear that the Western world, which bears almost all the responsibility for the climate disaster, does not care at the same time.

In June 2015, the state of emergency in Alto Huallage in the San Martín region was lifted, 30 years after it was introduced in the hunt for Sendero Luminoso partisans.

Despite a police ban in January 2015 against the use of deadly weapons in civil unrest, 12 protesters were killed by police in the first 9 months of 2015. There were often rural demonstrations against mining or other major infrastructure projects. In April, police planted false evidence on an arrester who had been captured during popular protests against a mine in Islay. However, journalists had videotaped the incident. The video was released and police forced to release the unlucky arrestor.

In April 2016, Peru held parliamentary and presidential elections. The parliamentary election was won big by the conservative Fuerza Popular (FP) who got 36.3% of the vote and 73 out of the parliament’s 130 seats. In second place, leftist Frente Amplio (FA) got 13.9% of the vote and 20 seats. In the presidential election, Keiko Fujimori from the FP got 39.9% of the vote, while Pedro Pablo Kuczynski from the equally conservative Peruanos por el Kambio (PPK) got 21.1%. Frente Amplios (FA) Verónika Mendoza got 18.7%. The two top candidates had to run out in the second round of the June presidential election. It was narrowly won by Kuczynski, who got 50.1% of the vote. It was a matter of tactical voice casting. Fujimori was the daughter of former president and war criminal Alberto Fujimori, who remains jailed for his crimes.

Kuczynski was inducted as president in July. That same month, Independent Fernando Zavala Lombardi was inaugurated as Prime Minister.

Thousands demonstrated in Lima in August in protest of the widespread violence against women. In the period 2009-15, over 700 women were murdered.

In December, the first news broadcast was broadcast exclusively on Quechua, spoken by 1/3 of the population. Although the language was recognized as one of the country’s official languages in 1975, it continued to live in the shadow of Spanish. It took over 500 years from the Spaniards to conquer the Quechua speaking inquisitor until the language was again recognized as a tool in the media. (Peru airs news in Quechua, indigenous language of Inca empire, for the first time, Guardian 14/12 2016)