Russia is a country located in Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It has an area of 17,098,242 square kilometers and a population of approximately 146 million people. The ethnic composition of Russia is mainly Russian, with other minority groups including Tatars, Ukrainians and Bashkirs. The majority of the population are adherents to Christianity, with around 70% following the religion and the rest being either Muslim or other faiths. Education is compulsory for children up to the age of 17 and the literacy rate is estimated to be around 99%. The official language is Russian but there are also many other languages spoken throughout the country such as Tatar, Ukrainian and Chuvash. The capital city Moscow has an estimated population of over 12 million people making it the largest city in Russia. Check hyperrestaurant to learn more about Russia in 2009.

Social conditions

Labor market and economy

Informal economics in the Russian Federation is a relatively comprehensive sphere that includes corruption, non-payment of taxes and work without a labor contract. Those who work in the informal economy make up 20.5 percent of the total workforce (2015). The largest proportion of employees in the informal economy can be found in the construction, trade and service sectors.

Falling oil prices have affected the Russian economy. Oil and natural gas are the country’s most important export products, and the fall in prices that started in 2012 has had a negative impact on the country’s economy. Also, sanctions imposed by other nations against the Russian Federation after the annexation of Crimea make the economy strained.

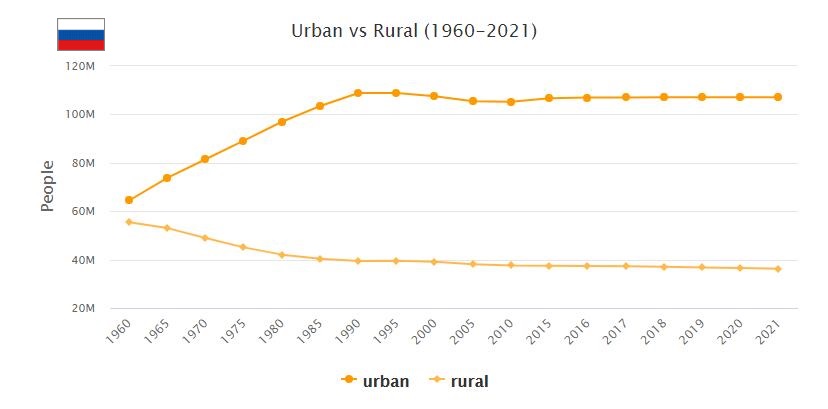

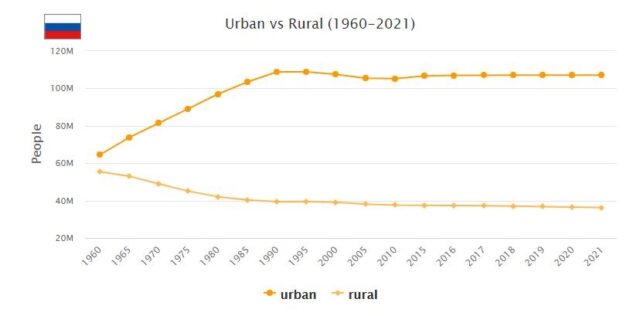

During the 2000s, the country’s economy improved, resulting in more jobs. In 2015, the registered unemployment rate was 5.6 percent, compared with 2010 when it was 10 percent. Check to see Russia population.

During the 1990s, a large proportion of the educated population emigrated. In the 00s, however, labor migration to the Russian Federation increased. Migration growth was 2.2 percent in 2011. Around half of migrants (3 out of 7 million) are illegal.

Economic crime has remained a serious problem in the country.

Welfare and poverty

In Soviet times, research and education, health care, pensions, child allowances etc. were funded through the state budget and by the state-owned companies. However, during the perestroika and glasnost, the planning economy was dissolved and its social security system reduced. The market economy policy, with major elements of corruption that has existed in the Russian Federation since 1992, led to sharp cuts in government spending, at the same time as companies cut their social costs. Economic reforms led to widening social gaps in society.

The Russian Federation is one of the countries where the difference between the richest and the poorest is among the largest in the world (2016). However, the Russian middle class is on the rise and has grown ever since. Calculated by income per capita per month, translated into euros, the social stratification in 2015 looked as follows: rich (more than 800 euros) 10.2 percent, well-off (266-800 euros) 43.4 percent, average (120-226 EUR 20.1 percent, low-income earners (EUR 67-120) 8.9 percent and extremely poor (less than EUR 66) 2.4 percent.

The proportion of people living below the poverty line fell from 40 percent to 13.1 percent between 1999 and 2010 and remains at this level today.

Equality

Women often have lower wages than men in the Russian Federation. In 2014, the gender pay gap was 23 percent. Men and women have the same terms for holidays, but the retirement age differs for men and women: women retire when they are 55 and men when they are 60 years. Visit AbbreviationFinder to see the definitions of RUS and acronym for Russia.

In childbirth, the woman has the right to be free with her child 140 days (70 before birth and 70 after) with full pay. One of the parents (as well as a grandparent) has the right to stay home with the child until the age of 3. However, the financial support during the leave with children is low. It is rare for parents to share parental leave and for fathers to be home with their children. As much as 98 percent of this leave is usually taken out by women.

Healthcare and health

The infant mortality rate was 6 per 1,000 in 2017, which is a radical reduction compared to 2000 when the corresponding figure was 15 per thousand. This is primarily due to improved finances and a state program for improved maternity care.

The government spent 7.1 percent of GDP on health care in 2014, which is slightly more than 2000 when the figure was 5.4 percent.

The number of HIV-infected people is growing and 1 percent of the population is HIV-infected. In spite of this, the government has in recent years withdrawn support for courses on sexual information and actively advocates heterosexual relationships and family life.

Per capita alcohol consumption in the Russian Federation is almost the highest in the world (fourth place according to WHO 2014). In 2015, however, consumption of alcohol decreased slightly compared to the previous year.

The Russian social reality is very difficult to read from public statistics, since it is very much an informal society.

Economic problems

Although Khrushchev’s successors annulled many of his administrative reforms, economic reforms were nevertheless carried out on a cautious scale, which had been debated among Soviet economists for several years. The individual companies were given greater independence in relation to the central planning body – Gosplan. In addition, as previously, the efficiency of the companies should not be measured by the physical scope of production, but by their profitability, ie. the ratio of resources used – inputs in the form of raw materials, machinery and labor and output measured in terms of the value of the output sold.

These reforms were later gradually canceled. But among the Soviet economists, there has always been extensive debate for various economic reforms. This became increasingly necessary as the annual growth rate dropped. While the increase in gross domestic product according to. North American sources averaged 6.4% in the years 1950-58, it had dropped to 3.4% in the late 60s. The main problems of the Soviet economy were the low utilization of resources and the low labor productivity – approx. one-sixth of the North American.

At the same time, the USSR was largely forced to import Western technology. In 1970-75, the country imported nearly 2,000 complete industrial plants. This resulted in huge deficits in the balance of trade with abroad, and the country accumulated a heavy foreign debt in convertible currency. Imports were moderately dampened somewhat in the late 1970s, but at the same time agriculture problems were far from resolved, and the USSR therefore had to spend large sums on grain purchases in the West to feed its population.

Internal opposition

The fall of Khrushchev and the suspension of the Stalinisation process led to the first opposition appearing in the USSR – originally as a protest movement among liberal intellectuals. The first underground publications, Samizdat, also date from this time. In 1969, a human rights action group was formed. The opposition – or “dissidents” as they were often called – represented a diversity of political and philosophical views. They were often classified into three groups by the most well-known leading dissidents – Sakharov, Solzhenitsyn and Medvedev.

Sakharov was arguably the most prominent dissident after Solzhenitsyn was sent to the West in 1974. Sakharov advocated a liberal, bourgeois-democratic policy, and was a strong defender of human rights.

Solzhenitsyn regarded Marxism and the entire Western European influence in Russia as the cause of the problems and oppression. He wanted to return to the beliefs of the Russian Orthodox Church and the traditions of the old Russian peasant community.

Roy Medvedev was the least known among the leading opposition. He was a more typical politician than Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn, and considered himself a Marxist and supporter of democratic socialism. Unlike Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn, he strongly supported the policy of relaxation.

Although dissidents like Sakharov and Medvedev were few and relatively isolated in the Soviet society, the various opposites in the Union Republics had a larger truly potential mass base. In several of the Union republics, human rights committees were formed in the 1970s. The most troubled of these republics was Lithuania, where in 1973 there was an open confrontation between population and police. In Ukraine, the opposites were considered to have widespread passive support among the population, as was the case in Armenia and Georgia.. In Tiblisi, in April 1978, thousands demonstrated against Georgian not being mentioned as the Republic’s language in the recently published draft new constitution. The party leadership immediately retreated according to the requirement of Georgian as the official language of the Republic next to Russian.

1985 Glasnost and perestroika

Mikhail Gorbachov assumed the post of Secretary-General of the SUKP in 1985 and initiated a series of in-depth reforms to curb the country’s severe social and economic crisis. The international political language was enriched with two new words: Glasnost – the Russian word for openness, which should mark greater openness in Soviet political structure; Perestroika – the Russian word for restructuring intended to mark a comprehensive restructuring and democratization of the Soviet economy. But Perestroika came too late and did not go far enough to contain the crisis, and Glasnost became a double-edged sword in particular, opening up the country’s unresolved national conflicts and contributing to the development of local demands for autonomy.

Glasnost was put on its first international trial in April 1986, when the Chernobyl nuclear power plant outside Kiev, Ukraine, burst into air. It was several days before the Central Committee of the SUKP received fairly accurate information on what had actually happened, and even more before the Soviet began to admit the catastrophic scale of the disaster. 135,000 people had to be evacuated from the area around the plant, and by 1993, 7,000 had died from radiation damage from the accident.

Despite the nuclear accident, the Soviet Union was able to recapture a significant part of the US diplomatic initiative, which had played a dominant role on the international scene in the first half of the 1980s. With his far-reaching proposals for nuclear disarmament, Gorbachov forced US President Reagan to the negotiating table, and again succeeded in getting the disarmament started. A development that was largely attributed to the Soviet Union. At the same time, the superpower decided to withdraw its forces from Afghanistan, where since 1979 they had been deeply involved in the country’s civil war. The last Soviet troops were withdrawn from the country in 1989. In 90, Gorbachov accepted the reunification of the two German states after East Germanythe year before had broken down. In the same year, he proposed a gradual dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and of NATO. The Warsaw Pact would later be dissolved – but NATO persists.

1991 SUKP dissolves

In June 1991, Boris Yeltsin was elected President of Russia, and in August he joined and dissolved the SUKP. A few weeks in advance, the most conservative wing within the party had conducted a coup d’etat and deposed Gorbachov – apparently supported by Yeltsin. 10 days later, Yeltsin changed sides, the coup collapsed and a severely weakened Gorbachov returned to Moscow. Yeltsin took advantage of the polarized situation to make his own coup in the coup: the SUKP was dissolved after holding power in Russia for over 70 years.

Even before the coup d’état, disturbances had broken out in Chechnya, demanding greater autonomy for Moscow. In late October, parliamentary and presidential elections won by Dzhojar Dudajev, leader of the nationalist Chechen movement. In early November, he declared the independence of the Republic of Chechnya. It was immediately met with economic blockade on Moscow’s side, with his Chechen compatriot Ruslan Kasbulatov presiding over the Russian parliament.

The Soviet Union disintegrates

On October 6, Jegor Gaidar of Yeltsin was appointed Deputy Prime Minister and initiated an economic shock therapy. At a meeting on December 8 with the participation of Boris Yeltsin of Russia, Stanislav Shushkevich of Belarus and Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine, the 1922 Treaty was repealed, which had formed the basis for the existence of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union no longer existed, but had been replaced by the Association of Independent States (CIS). Foreign policy Russia took over Soviet representations. In the Baltics, Latvia, Estonia and Lithaun detached themselves and were recognized by the UN as independent states. It happened without much violent resistance from Russia.

By the end of the year, Yeltsin and his reform movement had consolidated their power in society and in parliament. At the beginning of 92, the relationship between the two main CIS members, Russia and Ukraine, was marked by ever-stronger rivalry in the questions of the future of the nuclear arsenal, the future of the Soviet navy and the development of the Crimean peninsula. President Yeltsin declared that the United States was no longer Russia’s strategic rival and that Russia would continue its economic reforms. Prices were given free and industry, agriculture and trade were privatized.

The “rioting” between the president and parliament continued, in March 93 Parliament opposed a proposal by Yeltsin to hold a referendum, and at the same time tried unsuccessfully to limit his power. After new quarrels, Yeltsin deprived Parliament of all power. It responded by dismissing the president and replacing him with Alexandr Rutskoi. On the same day, September 22, police forces surrounded the Parliament. Tensions continued to rise, and on October 4 Parliament was taken in after being fired with tanks. Several opposition leaders include Deputy Speaker of Parliament, Rutskoi and its chairman Ruslan Kasbulatov were arrested. A few days later, Yeltsin printed a new election and organized a referendum aimed at strengthening his own power.

1994-96 War in Chechnya

In the December elections, the Yeltsin-friendly sectors suffered defeat, but at the same time he gained 60% of the vote in support of his constitutional amendment, giving him extended powers of power. In February 94, Russia entered into a bilateral agreement with the Russian Republic of Tartarstan, which, after Chechnya, was among the Russian republics that most strongly argued for increased autonomy. It was planned to enter into a similar agreement with Chechnya, but instead the relationship between the two parties became even worse, and in December 94 Yeltsin ordered the Russian army deployed against the detachment republic.

Despite international and national protests, the Russian president continued the military attacks on Chechnya’s capital Grozny, which in 1995 was almost completely destroyed. In December, the Communist Party, led by Genadi Zhuganov, won the election to the Russian parliament, the Duma, with 22.3% of the vote followed by the right-wing Democratic Liberal Party led by Vladimir Shirinovski with 11.8%. Russia Our Home led by Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin had to settle for 10.1% of the vote.