Bangladesh is a South Asian nation located in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta with a population of over 161 million people. The majority of the population is ethnically Bengali, with a notable minority of Rohingya and other ethnicities. Islam is the predominant religion, with over 90% of citizens identifying as Muslims while the remaining 10% are followers of Hinduism or other religions. The official language is Bengali, but English and Urdu are also commonly spoken. Most Bangladeshis live in rural areas and work in agriculture rather than industry or services. Poverty levels have been steadily decreasing since 2010, with the unemployment rate currently at 4%. Check hyperrestaurant to learn more about Bangladesh in 2009.

Social conditions

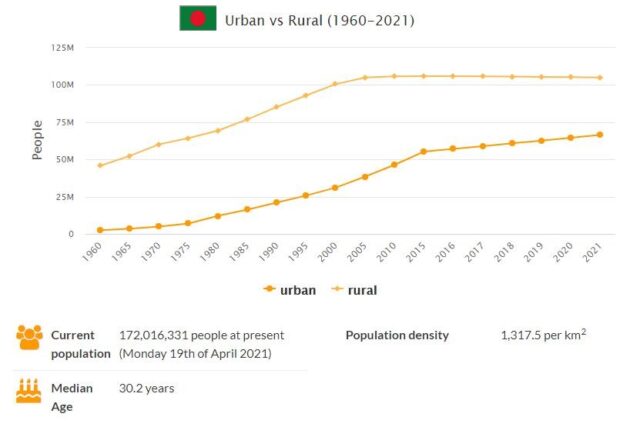

Scarce resources characterize most Bangladeshi everyday lives. For starters, this applies to physical space; with its 160 million residents on an area less than a third of Sweden’s, Bangladesh is one of the world’s most populous countries. Visit AbbreviationFinder to see the definitions of BGD and acronym for Bangladesh. Attempts to limit the nativity have been successful in recent years, but the population structure, with more than half younger than 25 years, still causes the number of residents to continue to increase. Given that agriculture is the sector that employs the most people, access to land and climate change are critical factors in the overall picture. More and more people are looking for cities, whose slums are growing, and jobs in industry, even abroad. Referrals (money that foreign workers send to their families) are a substantial part of the budget. Check to see Bangladesh population.

| Land area | 143,998 km² |

| Total population | 162,650,853 |

| Residents per km² | 1,129.5 |

| Capital | Dhaka |

| Official language | Bengali |

| Income per capita | $ 4,200 |

| Currency | Taka |

| ISO 3166 code | BD |

| Internet TLD | .bd |

| License plate | BD |

| Telephone code | +880 |

| Time zone UTC | +6 |

| Geographic coordinates | 24 00 N, 90 00 O |

In the industrial sector, textile and clothing manufacturing is the most important branch. Wages do not cover normal living expenses and working conditions are substandard, which was put into sharp light when over 1,100 workers were killed in a factory fire outside Dhaka in April 2013. Most, as in the rest of the industry, were young women. Despite advances in education and access to maternal care, women remain particularly vulnerable. However, the declining poverty in recent years and increased visibility in political life have, however, been important factors in strengthening women’s relative position, a process that has manifested itself in, among other things, increased life expectancy for women. (See also Human Rights.)

Poorly functioning public institutions, abuse of power and corruption are hostages to the population. The family is the hub of existence and most marriages are arranged, which helps keep the families together. However, traditional patterns are loosened up as society is modernized and industrialized. Civil society and various NGOs play an active and often constructive role. An example is Grameen Bank, which provides microcredit to the poor in rural areas, mainly women.

Bangladesh: behind the factories of death

The textile sector in Bangladesh is a huge opportunity for economic development and poverty reduction. But the poor working conditions highlighted by the Savar tragedy require stricter regulations and the implementation of minimum standards of wages, safety and workers’ rights.

The tragedy of the collapse of Savar’s Rana Plaza, the latest in a long series of accidents at work in Bangladesh, has reopened the debate on globalization, relocation and working conditions in developing countries. Tragedies like Savar’s shake public opinion, highlighting the most pernicious aspects of the process of international economic integration. However, in elaborating the responses to these events, it is necessary to consider a simple premise: for countries such as Bangladesh, the growth of the textile sector, which began in the mid-1980s, has been a huge opportunity for economic development and poverty reduction.. Wages, although very low compared to other countries, still allow a substantial improvement in the standard of living for a large segment of the population. This is especially true for women, traditionally excluded from the productive sectors. The most reliable research shows a strong impact of the development of the textile sector not only on women’s employment and wages, but also on education rates: in response to better employment prospects, families of girls who have access to textile companies invest more in the education of their daughters.

Too often, however, this premise is used by enthusiasts of globalization as an argument against any other type of consideration. But poor working conditions and hundreds of white deaths require more elaborate thinking and interventions in addition to the ‘invisible hand’ of the market. First, it is important to underline that labor codes and other regulations often exist, but are not enforced; limited administrative capacity and corruption determine this situation.

Furthermore, inspection agencies are often funded by the same companies that they are supposed to monitor.

Recent studies conducted in India on another field of inspection, that of the environmental regulation of companies, quantify the pathological state of these mechanisms. These studies also reveal that simple and inexpensive measures, such as randomly assigning inspectors to companies and creating an incentive system for correct pollution measurements, have a significant impact on companies’ compliance with environmental standards. The need to ‘control the controllers’ is just as important as writing the rules on paper.

The role of international organizations, such as the International Labor Organization (ILO), in promoting and enforcing minimum standards is often a matter of debate.

The Better Factories Cambodia program is perhaps the prime example in which ILO involvement has yielded important results on indicators such as child labor, how wages are paid, facility safety and entitlement to maternity leave. The program aims to help businesses through the costly process of improving working conditions by combining monitoring with training and consulting for the workforce and business management, with the aim of increasing productivity. The positive results obtained in Cambodia led to an expansion of the same program in Vietnam, Nicaragua, Jordan and other countries. Civil society in the Western world is another of the actors involved, above all through its consumption choices. The view that the simple boycott produces more risks than benefits is prevalent among industry experts. On the contrary, the development of consumer demand for certified products (think of the best known case of Fair Trade) allows the creation of a differentiated market. The most recent experimental studies, conducted in shopping malls in the United States even in areas that are not particularly affluent, analyze the willingness of consumers to pay for certifications of various kinds and lead to cautious optimism. In addition, in response to recent events and consumer demands for guarantees regarding workers’ conditions, an increasing number of multinationals are signing agreements regarding safety standards and working conditions. However, the scope and effectiveness of these measures remain open questions. For example, some major US manufacturers did not sign the recent agreement on firefighting measures in Bangladeshi factories. In addition, following the Savar collapse, many companies, including Italy’s Benetton, have admitted that, due to the intricate network of subcontractors in the production chain, it is in fact very difficult to monitor where exactly production takes place. Paradoxically, support for local workers’ organizations is rarely a priority for Western activists. However, the strengthening of these organizations, and therefore of a daily system of monitoring and reporting abuses, is essential for the improvement of working conditions. In Bangladesh, as in other countries, intimidation and firing of workers active in the nascent trade union movement are on the agenda. The most controversial case concerns the killing of local activist Aminul Islam, who was tortured and killed in April 2012. Although there are strong suspicions that his death is linked to trade union activity, the perpetrators have not been identified to date. Given these premises, the new law that in Bangladesh guarantees the right of association without first obtaining the authorization of the employers is probably the most important result for an improvement in the conditions of workers among those made in recent months.