State breakdown of Australia

Australia is a federal parliamentary monarchy within the Commonwealth. The head of state is the English queen. The state of Australia comprises 6 states and two territories, each with its own administration. See Countryaah.

Population distribution and development

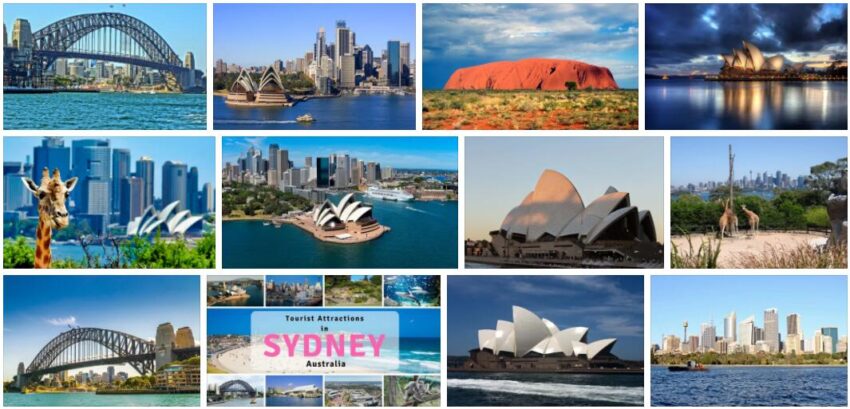

With a population density of around 2.5 inhabitants/km², Australia is one of the countries with the lowest population density. The population is very unevenly distributed across the continent. 85% of all residents live in cities, especially in the east and southeast, which belong to the largest metropolitan area in the country (Fig. 8).

In total, nine tenths of Australians live in only 3% of the area.

Almost the entire western and central parts of the continent are only sparsely or not populated at all. Between 1990 and 1996 the population growth was around 1.2% per year. Natural growth was much lower, however, as a significant number of immigrants, especially from Great Britain and New Zealand, had a clearly positive impact on the growth rate. The Australians are 95% of European origin or are their descendants. Three quarters of all Australians have British or Irish ancestors. Since the termination of the “White Australia Policy” in 1973, Australia has become a more immigration country again. The proportion of immigrants from Asian countries has increased in recent decades, particularly from China, Vietnam and Indonesia.

| Country | Proportion of women in Parliament (percent) | Public Expenditure on Health Care Per Person (US Dollar) |

| Australia | 29 (2018) | 5,002 (2016) |

| Fiji | 16 (2018) | 180 (2016) |

| Kiribati | 7 (2018) | 188 (2016) |

| Marshall Islands | 9 (2018) | 851 (2016) |

| Micronesia Federation | (2018) | 387 (2016) |

| Nauru | 11 (2018) | 1,012 (2016) |

| New Zealand | 38 (2018) | 3 745 (2016) |

| Palau | 13 (2018) | 1 674 (2016) |

| Papua New Guinea | (2018) | 55 (2016) |

| Solomon Islands | 4 (2018) | 106 (2016) |

| Samoa | 10 (2018) | 227 (2016) |

| Tonga | 7 (2018) | 203 (2016) |

| Tuvalu | 7 (2018) | 507 (2016) |

| Vanuatu | (2018) | 110 (2016) |

The Aboriginal people

The indigenous people of Australia, the Aborigines. With the possession and settlement of the continent by Great Britain, the Aboriginal people began a more than 200-year history of suffering. The British settlers declared Australia to be “terra nullius”, “land that belongs to no one”, despite the fact that the Australian natives had lived here for at least 50,000 years. In search of agricultural areas, Europeans ruthlessly destroyed the traditional way of life of the indigenous people. Many tribes were either exterminated with the weapon or introduced diseases, or they were forcibly placed in reservations and committed to working on farms. Children were separated from their mothers at an early age in order to raise them “white” in white families or nursing homes. Even today, many tribes are threatened with extinction: it was only in the 1960s that the Australian natives won their recognition as Australian citizens and the right to vote.

The almost 466,000 Australian aborigines are today the minority and “subclass” in the affluent state of Australia with a population share of about 1.5%. Despite formal legal equality, they still have little say in the matter and are still subject to separate case law in court. In addition, unemployment, low levels of education, low life expectancy and alcoholism often determine their everyday lives.

Nevertheless, after many Aboriginal people have denied their origins for fear of discrimination, more and more Australian Aborigines are beginning to consciously acknowledge their origins and revive their traditions and language.

Agriculture

The settlement of Australia began with the establishment of a penal colony in 1788. The aim and idea of the Europeans was to create an agricultural system based on the English model, which was largely independent of the mother country. The climatic unfavorability of the country soon set clear limits for agriculture. Nevertheless, agriculture was and still is the most important economic branch in the country. Today it is highly mechanized and uses around 65% of the country’s area.

The main branch is sheep and cattle breeding, since the lack of water and, above all, the irregularity of the rainfall set narrow limits for agriculture.

Only 4% of the area can be used for intensive irrigation farming. Cultivated products are wheat, sugar cane, cotton, barley and rye. A quarter of the export income is still covered by agricultural products such as wheat, sheep’s wool (about a quarter of the world’s production), beef, sugar and milk products. Overall, however, agriculture is losing economic importance.

Mining and industry

Australia is extremely rich in mineral resources. The mining sector is therefore becoming increasingly important economically.

Australia is one of the leading producers and exporters of coal, petroleum, natural gas, uranium, nickel, iron ore, bauxite, gold, copper, nickel and tin. Mining accounts for one third of its products in exports. Around half of Australia’s raw material exports go to the Japanese market.

Australia has a diverse industry, which includes almost all traditional branches of industry: including iron and steel production, vehicle and mechanical engineering, the food industry as well as the chemical and electrical industry. The country generates a large part of its export earnings with its products. The main trading partners are Japan, the EU countries, the USA and New Zealand (Fig. 10.

History

1770: JAMES COOK takes over the east coast of Australia for Great Britain.

1788: Foundation of the first British penal colony in what is now Sydney.

until 1890: foundation of further British colonies.

1901: All colonies merged into one state, the British Empire Commonwealth of Australia.

1914–1918: support for England in the First World War.

1939–1945: Australia fights primarily against Japan on the Allied side.

1967: Civil rights for the Aborigines

1986: “Australian Act” – The British Queen loses the last legal ties between the Australian Confederation and Great Britain.

1993: “Native Title” – Aborigines are granted limited rights to their land.

1999: The referendum on the abolition of the monarchy in favor of a republic fails.

Literature of Australia

It was 100 years after the founding of the first English colony in Australia in 1788 before an independent literature of importance emerged. In this early period, the poets were patriotic and in part wrote about Australian subjects, but most often in a superficial and conventional way. The best lyricists were Charles Harpur, the quiet Thomas Henry Kendall and the somewhat uneven but very productive Adam Lindsay Gordon, who with the poem The Sick Stockrider thematically ushered in something new. Among the novelists are Catherine Helen Spence, Marcus Andrew Hislop Clarke, whose drastic account of the prisoners’ condition in Tasmania, His Natural Life (1874, His Natural Life), has become an Australian classic, and Rolf Boldrewood (pseudonym of Thomas A. Brown), whose Robbery Under Arms (1888) has numerous historical interest. Meanwhile, there was a mass production of shows (such as Waltzing Matilda) and gags at the folk, and here the Australian literature came to find much of its uniqueness and strength.

From 1886, the journal The Sydney Bulletin became the center for the flourishing of a true show and narrative art in the nationalist spirit, especially under the editors JF Archibald and AG Stephens. Among the contributors were the poet “Banjo” Paterson (real name Andrew Barton Paterson) and the Norwegian-born Henry Archibald Lawson, whose short stories initiated a new direction in Australian literature called bush realism, where the theme of mateship (camaraderie between men) was central. Tom Collins (pseudonym for Joseph Furphy) wrote a strange novel in diary form, Such is Life (1903, Such is Life), which depicts the lives of the drivers from a radical political point of view.

Later novelists include Louis Stone, with his novel about the urban disaster, Jonah (1911), and Miles Franklin, who wrote My Brilliant Career (1901, My Brilliant Career), about the farmer’s life from a woman’s point of view, and a great family novel, All That Swagger (1936).

Australia’s two leading female writers in the period leading up to World War II are Henry Handel Richardson (pseudonym of Ethel Robertson) and Katharine Susannah Prichard. Worth mentioning is the ingenious humorist Norman Lindsay, also a significant visual artist. His Red Heap (1931, Red Pile) was banned by the censorship. The versatile Vance Palmer is particularly remembered for his short story art; Frank Dalby Davison wrote the beautiful animal story Red Heifer (1931, Red heifer); Leonard Mann is known for his hard-boiled novels, such as The Go-Getter(1942, Strebes); and two female writers, Eleanor Dark and Kylie Tenant, have made their mark on their realistic novels with social and national historical themes.

Among those who have gained international importance in the 1960s and 1970s in particular are family chronicle writer Martin à Beckett Boyd, national epic Xavier Herbert, long-time failed Christina Ellen Stead and Nobel Laureate Patrick White. Other well-known names are the symbolist Randolph Stow, the autobiographical Hal Porter, the mouthy Morris L. West and the topographical-historical reporter Alan McCrae Moorehead; moreover, Thea Astley, George Johnston, Thomas Michael Keneally, Peter Mathers and David Malouf.

And while the 1970s saw the emergence of a new generation of male short story writers, such as Murray Bail, Peter Carey, Frank Moorhouse and Michael Wilding, the 1980s were marked by a number of new, talented female writers, including Glenda Adams, Helen Garner, Kate Grenville, Barbara Hanrahan and Elizabeth Jolley (who, like Wilding, were originally from the UK).

The later lyricists have, to a large extent, been intellectually distinguished: Bernard O’Dowd, advocate for the trend of poetry and for a particular Australian socialism; the experimental Furnley Maurice (Frank Wilmot); Clarence James Dennis, with his folk dialect and humor; the community- committed Mary, Dame Gilmore; Hugh Raymond McCrae, a picture-drinking and romantic lyricist; John Shaw Neilson and Christopher John Brennan.

Modernism made its entry into Australian lyric with Kenneth Slessor, who for a time was strongly influenced by TS Eliot, and Robert David FitzGerald, known for his philosophical-argumentative poems. Alongside these, modern Australian poetry has experienced a flourishing that is not least due to Judith Arundell Wright, Douglas Alexander Stewart, James McAuley, Rosemary de Brissac Dobson, AD Hope and Francis Webb. Leading names from the 1980s are Les Murray, who is dedicated to highlighting the importance of poetry in everyday life, and Bruce Dawe, if journalistic lyricism takes its time on the pulse. Robert Adamson and John Tranter have written more experimental poetry, while Robert Gray continues the “novelty” in the lyrics.

The drama got a new go after Ray Lawler’s success with The Summer of the Seventeenth Doll (1955, The Summer of the Seventeenth Doll). David Williamson has developed a kind of journalistic drama based on current political topics. He uses Australian everyday language with great success, while touching on ingrained notions in the collective consciousness. Other playwrights of significance are Jack Hibbard, Alex Buzo, Peter Kenna, Louis Nowra and Steve J. Spears. In addition, Douglas Alexander Stewart, Patrick White and Thomas Michael Keneally have also excelled as screenwriters.

Among non-fictional works include Robyn Davidson’s Travel Description Tracks (1980, Tracks), an account of her wandering with her camels across the Australian continent, Patrick White’s autobiography Flaws in the Glass (1981, Cracks in the Mirror or Distorted Mirror), and the autobiography A Fortunate Life (1981, A Lucky Life), written by the autodidact AB Facey (1894–1982) and dramatized in 1985. CEW Bean (1879–1968), a significant contemporary historian, wrote about Australia’s participation in the First World War.

Aboriginal poetry

A new element has emerged in Australian literature in recent decades, namely the poetry of indigenous peoples. Previous literature on this people was either documentary novels and travelogues written by whites telling about their experiences among the aboriginal people, or collections of myths and legends adapted to European tastes, such as Catherine Langloh Parker’s Australian Legendary Tales (1896, Australian Legendary Adventures) and Alan Marshall’s People of the Dreamtime (1952, The People of the Dreamtime). Nevertheless, such works can be said to have had their mission by providing readers with valuable insights into the Aboriginal oral narrative tradition and complicated world of performances, and by arousing interest in their culture.

David Unaipon’s Native Legends (1929, Ur Legends) was the first book written by an Aborigine published in Australia. From the 1960s, however, Aboriginal voices have been expressed in most literary genres. Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Kath Walker) published his first collection of poems, We Are Going (We go), in 1964, and the following year came Narogin Mudrooroo (Colin Johnson) with his first novel, Wild Cat Falling (Wild cat falls). Kevin Gilbert’s Living Black (1977, Black Life) was an important work that began a period of several releases by Indigenous people. Jack Davis has written several acclaimed plays, and in her poignant autobiography, My Place (1987, My Place), Sally Morgan portrays her quest for identity and the discovery of her family’s history. The book is also an important social and cultural history document. Archie Weller, who has written several novels and fine short stories, and Ruby Langford Ginibi, a renowned autobiographical writer, are also poets who promote the cause of Aborigines. Much of this literature is politically marked. Today, texts by indigenous writers are an integral part of Australian literature and the subject of critical studies in line with other works. And from the 1990s we see a new wave of literature written by Aborigines, not least autobiographies.

Cultural diversity

Writers with a different background from the Anglo-Celtic have made important contributions to Australian literature in recent decades. Much of this poetry from the 1960s and 1970s is found mainly in literary magazines and magazines. It is only in the 1980s that we find several texts written by non-Anglo-Celtic authors published in book form. Famous names are Brian Castro, Aina Walwicz and critic Sneja Gunew. Others mentioned are Dimitris Tsaloumas, who wrote in Greek, Serge Lieberman and Sreten Bozic, who wrote under the pseudonym Banumbir Wonga in the 1970s and 1980s. However, it was not until the 1990s that these authors were recognized and regarded as representative of the cultural diversity found in Australian society. Today, there are hundreds of writers with a multicultural background who contribute to the diversity of Australian literature.