In the century that runs from the opium war to the Second World War, the attempt to rediscover one’s own identity as a nation and culture has materialized in China in more or less happy episodes, some developed in politics, others above all in terms of ideas. In this context, around the mid-nineteenth century, the revolt of the T’ai-p’ing (triggered by the preaching of Hong Hsiu-chuan, who was believed to be the brother of Jesus Christ) who for a brief moment was on the point of overthrowing the Manchu dynasty and was then defeated, thanks also to the support that the Europeans believed they had to provide to the Celestial Empire against the rioters, although these, even if in a singular and confused way, they declared to refer to so many ideals of the West. The T’ai-p’ing were, on the one hand, the updated repetition of many peasant revolts that distinguish Chinese history and the decline of all dynasties, but they were also a first confused attempt at national revolt in a country that had not never known a nationalist dimension and, finally, the attempt to merge western and autochthonous elements in a confused syncretism to find a way exit to the crisis in which the Chinese world was struggling at the level of political and economic situation and at the level of awareness of its own entity and culture. In this period, the British freighter incident Arrow offered Europeans a new pretext to intervene.

In addition to Great Britain, Russia and France participated in the hostilities against China, a country located in Asia categorized by Ezinesports. Chinese resistance was almost nil; after the occupation of Canton (1857), the Western powers attacked the forts of Ta-ku in front of Tientsin and in 1858 the Treaty of Tientsin was concluded between the belligerents, which provided for China with serious conditions. In 1860 an attempt to avoid ratification of the treaties caused a resumption of hostilities. In this new phase, the Summer Palace was destroyed and China, forced to capitulate, received Western envoys to ratify the 1858 Tianjin Accords completed by the Beijing Additional Convention . (1860) with which new concessions were obtained. The last T’ai-p’ing disappeared between 1864 and 1866, at the end of the century the doctrinal utopianism of K’ang Yu-wei it seemed for a brief moment that China could be saved thanks to a constitutional conception of the monarchy and a “modernized” vision of Confucianism. After the Chinese defeat in the war against Japan (1894-95), the victors imposed severe economic sanctions and heavy territorial concessions (which, in part, were not implemented due to the Russian veto). The Western powers, both taking advantage of the weakness of the empire and not to lose ground, grabbed more and more concessions. Thus a division of the country into areas of exclusive influence took shape: France assumed substantial control of the southern provinces; Great Britain of the central ones; the central-northern Germany around the Shantung peninsula; finally, Russia of the continental provinces, such as Manchuria.

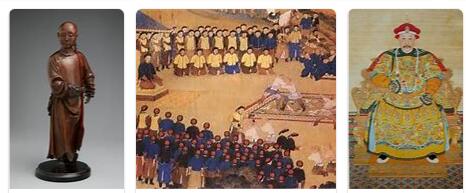

Only the opposition of Great Britain, the United States and Japan (whose policies converged on this point, despite the divergence of interests) prevented an effective partition of the Chinese territory. Inside, while K’ang Yu-wei’s attempt at reform was consummated (between 1896 and 1898), knowledge of the Western world became more serious and deeper thanks to the popular work of travelers and scholars who had been in Europe or knew the works of European culture (such as Lin Shu or Yen Fu). Western political and scientific thought advanced in the consciousness of the Chinese and created new ferments which, linked to the increasingly widespread discontent and the drama of the conditions in which most of the population found themselves, generated attempts at revolt in which a confusingly modern inspiration was combined with traditional characters that linked these movements to the millenary peasant revolts. Evidence of these confused needs is the revolt of the Boxers, who promised to expel foreigners from the country. Initially their action was also directed against the Manchu dynasty, which was perceived as “foreign” on the basis of the ancient Confucian ideology; later, however, the dynasty (whose destinies were summed up in this span of years in the widowed empress Tz’ü-hsi and in the general Yüan Shih-k’ai) succeeded in exploiting the xenophobic inspiration and transforming the Boxers into ardent loyalists of the Mancesi. The parable of the Boxers dates from 1899, when they began to attack and slaughter first converts to Christianity and then the Westerners themselves, and 1900, when an international expeditionary force occupied Beijing and abandoned itself to the sack of the city. As an indirect consequence, the Boxers revolt put the institutional, economic and social equilibrium on which the Manchurian dynasty was based in serious crisis.